Let me start with blowing my own trumpet, it’s my blog so I’m allowed! I’m pleased to have tracked down a copy of Delicious Magazine while in Budapest because in it they have elected my book Pride and Pudding as one of the best books of 2016! After the hard work creating this book I am of course flattered and beyond happy to get this kind of news! So thank you again Delicious Magazine UK!!

Now on to the news of the day!

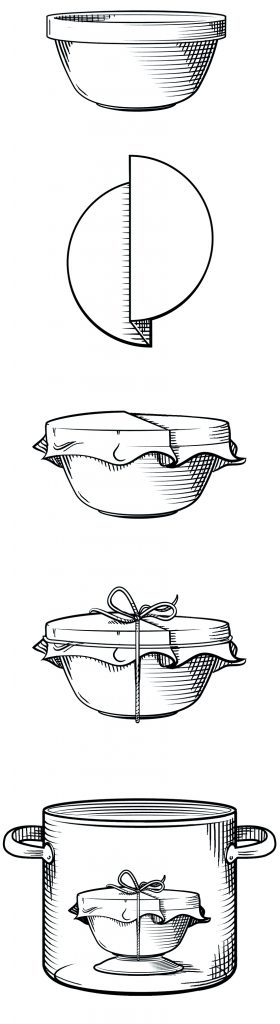

This weekend will mark the last Sunday before advent which is traditionally Stir-up Sunday. According to (rather recent) tradition, plum pudding or Christmas pudding should be made on this day. It is a custom that is believed to date back to the 1549 Book of Common Prayer (though it is actually not); where a reading states ‘stir up, we beseech thee’. The words would be read in church on the last Sunday before Advent and so the good people knew it was time to start on their favourite Christmas treat.

It was a family affair: everyone would gather to stir the pudding mixture from east to west, in honour of the Three Kings who came from the east. Sometimes coins or trinkets would be hidden in the dough; finding them on Christmas Day would bring luck and good fortune.

There are a lot of legends and claims made about the origins of the plum pudding. Some say it was King George I who requested plum pudding as a part of the first Christmas feast of his reign, in 1714. George I was christened ‘the Pudding King’ because of this myth but there are no written records prior to the twentieth century to tell us that this king deserved this title.

The first written record of a recipe for plum pudding as we know it today can be found in John Nott’s The Cooks and Confectioners Dictionary from 1723. There is, however, no suggestion that the pudding is associated with George I, the practice of Stir-up Sunday, or the Christmas feast.

In this era, plum puddings were a common companion to beef on festive days; they were eaten before or along with the meat, not after the meal topped with plenty of cream as we know it today. A plum pudding would often be sliced up and arranged under the dripping of a roasting joint of meat in front of the fire.

The ‘Hack’ or ‘Hackin’ pudding (recipe also in my book Pride and Pudding), a relative of the haggis and plum pudding from the north of England, was eaten in the same fashion. It is possible that the tradition of eating a plum pudding with roast beef on festive occasions evolved to it becoming the highlight of the Christmas feast, inspired by customs in the north of England.

By the Victorian era the Christmas pudding was well and truly the symbol of Christmas, although the Christmas tree would soon take its place. Printing methods improved and it became possible to print in various colours so Christmas cards became popular. Many of these depicted puddings as centrepieces on the festive table and cards featured puddings dressed up like little men.

The whole history of plum pudding is too long for a single posting – but you can read more about how it became the food to show your patriotism to Britain in the pages of my book. One thing seems for sure to me, Stir-up Sunday is a fairly recent tradition. But even though it’s not as old as the 16th century reading in the Book of Common Prayer, it has been around since Victorian times which makes it part of traditions today.

This recipe is based on early Plum pudding recipes but it evolved in my kitchen over the years. It really is no trouble at all making it so maybe this year you’ll give that M&S Christmas pud a miss and try your hand at your very own. In my book you’ll also find a war-time Christmas pudding, maybe I’ll share that recipe with you another year – or… get the Christmas issue of Vintage Life Magazine where you’ll find it!

Also listen to the Delicious Mag podcast here > to hear @deliciouseditor Karen Barnes talk about her mother’s recipe for Christmas pudding!

Or take a look at Jamie Oliver’s nan’s recipe here > with Vin Santo.

Hate Christmas Pudding (what’s wrong with you!!) then maybe this ‘Chocolate pudding for Christmas pudding haters’ by Nigella Lawson is your thing! It has hot chocolate sauce. One persons food hell is another person’t delight!

Not sure what to cook for Christmas dinner? I’ll share with you a traditional meal very soon! Here you’ll find some vegetable preparations that could come in handy.

Please note: This text is mostly taken from my book Pride and Pudding – The History of British Puddings savoury and Sweet (Murdoch Books 2016 – Davidsfonds 2015), as is the recipe below.

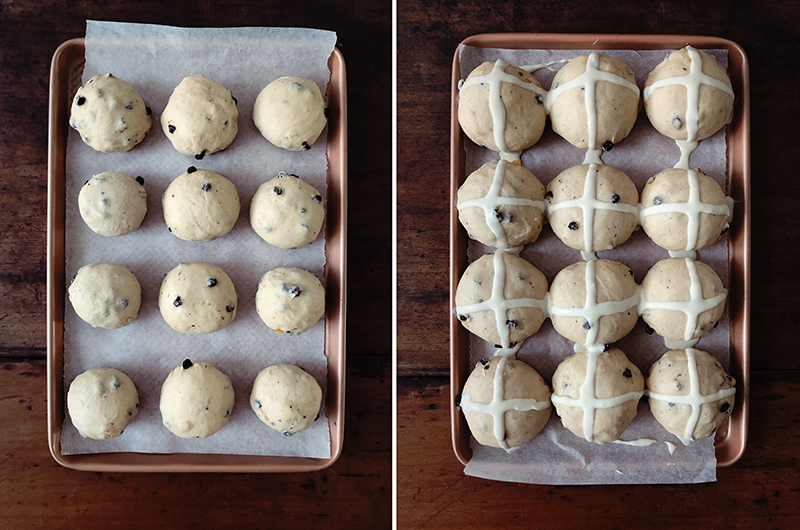

Bake them on Good Friday: The history and tales behind these spiced buns are plenty and intriguing, steeped in folklore dating back as far as Anglo-Saxon Britain. This is perhaps one of the most iconic of buns. Recipe from my new book Oats in the North, Wheat from the South, out with Murdoch Books (2020)

Bake them on Good Friday: The history and tales behind these spiced buns are plenty and intriguing, steeped in folklore dating back as far as Anglo-Saxon Britain. This is perhaps one of the most iconic of buns. Recipe from my new book Oats in the North, Wheat from the South, out with Murdoch Books (2020)