When I tell people about my passion for historical dishes, there are always those who look at me with disbelief and some amusement. They claim those ancient dishes were made of rotting meat masked with an abundant use of spices, or stodgy pottage, all eaten with the hands like barbaric creatures. It can’t be good, it can’t be imaginative, it just can’t be …

The theory that food in the Middle Ages was highly spiced to mask the flavour of rotting meat has been discarded as pure nonsense in the last ten years. Those who were served spiced dishes were privileged, those cooking with it were the master cooks to kings and queens. People of status that not only could afford this immense luxury, but also had a good supply of fresh meat and fish from their estates and beyond.

Our ancestors – of the elite – had a good understanding about spices, and how to combine them. Those flavour combinations would often taste peculiar to us. Not at all in a wrong way, but in a way that you realise it is a flavour sensation you have never tasted before.

This brings me to how tastes have changed.

Today everything is usually either sweet, salty or spicy. Bitter is making a modest comeback and sour too, but these flavours are seldom combined in our ‘modern’ European cuisine. It is even so that a lot of our foods are processed in factories which add flavour essences to make the food taste the same every time you prepare it. Of course this doesn’t happen when you cook from scratch, but it is an unfortunate fact that people in the UK buy a lot of ready meals. It is a trend that has luckily not taken off in Belgium, but it is very possible we’re not far behind. Joanna Blytham recently published a book about these practices in food processing factories, and she rings an alarm bell and employs you to smell your food, to taste, and realise the smells and tastes are not from natural ingredients. This is an evolution, when more people eat processed food, they get an idea about how tomato tastes, and how a beef stew should taste. It goes so far that when those people taste the real thing, they can’t take the sourness of a real tomato, the texture of the skin, and they find their own beef stew too bland and wonder where the flavour of the ready meal comes from. It’s not tomato, and it’s not beef. Butter in buttery pastry is not butter but other fats, with added butter flavour. It might taste like butter, but it might not completely and it might even change your taste and idea of how it should taste all together. I will go into Joanna’s eye-opening book in another posting but you get the idea for now. Today many of the people taste food, but don’t really taste the produce. Their tastes change. A very simple example is when I give someone a glass of raw milk to drink, I am used to it and drink it all the time, but my guests often can’t finish another sip because they find the flavour too ‘animal-like’. Most milk you buy in the supermarket to me tastes like white water, but this is how the people think milk tastes like these days.

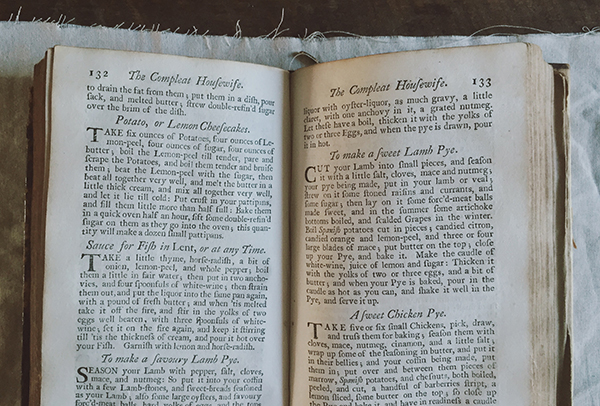

Eliza Smith’s Sweet Lamb pie from 1727 is one of those dishes that really show off the old way of spicing food. The flavours come through in layers if you get what I mean. It is not really sweet, but the spices that are used, nutmeg, mace and cloves were considered sweet spices and used as a sweetener. Sugar is added too, but used rather like a spice. In addition to these spices, currants and candied peel are added to bring extra sweetness. Then also sweet potato is added, and artichoke hearts. The 1727 book also mentions that when artichokes aren’t in season, one can use grapes too.

The pie is built with pieces of diced lamb, dusted in the spices, and meatballs made with lamb meat, suet, currants and the same sweet spices with the addition of fresh parsley.

Layers are constructed of lamb, lamb meat balls, sweet potato and artichoke.

When your pot or pie is full, a blade of mace is added and the pie is placed in the oven for just over an hour. Just when you’re ready to serve, a ‘Caudle’ is made, this is a sauce which is added to the pie by pouring it in when you are ready to serve. It is usually there to lift the flavours of the dish. In this case the caudle is made with white wine, lemon juice, a little sugar and a couple of egg yolks.

This sauce gives the dish a little acidic kick and will guaranty you to want to empty the saucepan until the very last drop.

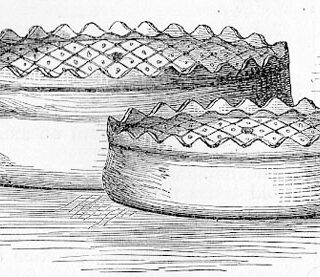

The pie can either be made in a free-standing pie crust like you see in the pictures I took when I was at Food Historian Ivan Day’s house, for a weekend of Georgian cooking last year. A hotpot is however another way of making this pie, this is a closed casserole dish used in the North of England, or you can use a deep oven dish and add a pastry lid, which is what I did the last time I made the pie, and what you can see in the first pictures here.

I made this Sweet Lamb pie not too long ago when we had two chefs coming for dinner, I did not know how they were going to react to the flavours of this dish.

Fortunately my friends are all about good, honest and natural food so they were eager to try. And they enjoyed it, one of the duo even asked me if it was okay to lick his plate and clean out the saucepan of caudle.

I say that’s mission accomplished, don’t you think?

The pie is incredibly flavoursome and eats just wonderful with the different vegetables and meat; the addition of a piece of salty pie pastry is a bonus but not a must if you aren’t up to making your pastry, but please don’t use shop bought pastry… that is just plain evil and doesn’t even contain butter!

I made the pie you see in the pictures above with pastry I had leftover from my recent pastry project… You might have spotted it on instagram.

18th century Sweet Lamb Pie

- 250 g lamb meat from the leg

- 250 g lamb mince (if you buy a leg, you can use the leftover leg to mince)

- 2 large sweet potatoes, parboiled, cut in dice

- 4 small or 2 large artichoke hearts, parboiled, cut in dice

- or when you don’t have artichokes, use a handful of grapes, blanched.

- 1 tsp of ground mace

- 1 tsp of ground nutmeg

- 4 cloves, beaten

- 2 blades of mace

- a generous pinch of good black pepper – or 3 pieces of long pepper, beaten

- 1 tsp each of candied lemon and orange peel, in small cubes

- 50 g of shredded suet

- fresh parsley cut finely, about 1 tbsp

- currants 50 g

For the Caudle

- The juice of 1 lemon

- The same quantity of white wine

- 1 tsp of sugar

- 1 egg yolk

- a little knob of butter

Preheat your oven to 160° C

Beat your spices, but leave the two blades of mace whole.

Dust the meat with half the spices, add the other half to the minced meat.

Make your minced meat balls with the spices, suet, parsley and 2 tbsp of currants.

Have all your components of the dish ready so you can start making the layers.

Place some meat, meatballs, sweet potato and artichoke into your dish or pastry and strew over some currants and candied peel, continue until the pie is full.

Close the pie with pastry, making a hole for steam, or put the lid on and pop in the middle of your oven for 1 hour to 1hr and 15 minutes. This could be longer, it depends on the quality of your meat, decent meat needs less cooking. So try and taste, when you have a pastry cover, user a skewer to prick to see if the meat is tender.

When ready, take out of the oven and make your Caudle.

Bring your wine and lemon juice to a simmer with the sugar, in a separate bowl, have the yolk ready and add the warm caudle like you would for a custard. Finish with a little knob of butter and warm again over the fire.

Pour the caudle into the pie, and serve. The caudle will mix with your pie juices and create a sauce.

If you’re making pastry, this is an easy recipe to try

For the pastry

- 300g plain white flour

- 100g unsalted butter

- 100g shredded suet

- a generous pinch of salt

- 125 ml ice cold water

- 1 egg, beaten

- Combine the flour, butter, suet and salt in a large mixing bowl and use your fingers to rub the butter into the flour. Keep on doing this until the mixture resembles breadcrumbs.

- Pour in the water and start pressing the liquid into the breadcrumb-like mixture. Be gentle as you must be careful not to overwork the dough.

- When you have created a rough dough, wrap it in cling film and let it rest in the fridge for an hour or more. You can prepare the pastry the day before if you’re feeling organised.

- Use the beaten egg to eggwash the edges of the piedish.

- Take your pastry out of the fridge and place it on a floured work surface. Now roll out the pastry about 1 cm thick and make sure it’s larger than your pie dish.

- Now carefully pick up the pastry and place it over the pie dish. Trim off the edges of the pastry so you get a nice lid. Now crimp the edges by using your thumb or a fork so the pastry lid is closed tightly. Make a hole in the middle so steam can escape.

- Decorate the pie lid if you like and eggwash generously before putting into the oven on one of the lower parts.

Serve with green asparagus if you have them, or green beans, or just as it is.

The pictures below were taken at Ivan Day’s Georgian cooking weekend in the Lake District