It is not a coincidence that I chose to write about Queen cakes today. If you’ve read the papers and watched the news, or if you are a royalist, then you know today the Queen of England celebrates her 90th birthday. This makes her the world’s oldest-reigning monarch and the longest reigning monarch in English history. Queen Victoria was the previous record holder with her 63 years and seven months. So Queenie has every reason to be smug and have a big party – which is a giant street picnic on the Mall (the strap of wide street in front of Buckingham palace) in june. Getting a ticket for it was near impossible to my regret, because this was a celebration I would have been happy to buy a new hat for, bunting I already have aplenty. So if you’re reading this Your Majesty… is there room for one more? I’ll throw in a book!

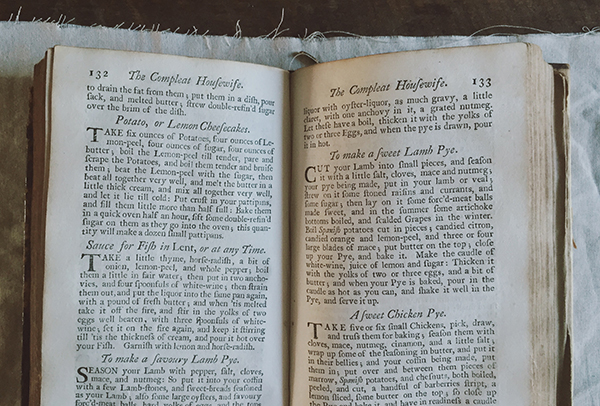

But let’s talk about these Queen cakes. They are little cakes, and they started popping up in English cookery books in the 18th century. When reading the several recipes from the 18th to the 20th century I have in original cookery books, they remind me of a little cake I grew up with in Belgium. However, the recipe was slightly different as the Belgian cakes were flavoured with a little vanilla or almond essence, while Queen cakes are flavoured with mace, orange flower water, rose water and lemon depending on the date of the recipe. The Belgian cakes also look more like Madeleines, but they both have currants in them and the use of vanilla or almond essence is of course a slightly more ‘modern’ way to flavour bakes.

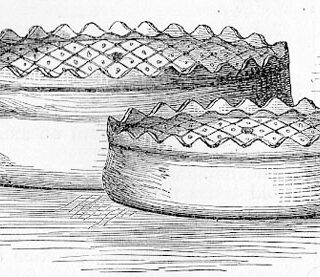

As with many English dishes, the Queen cakes come with their own dedicated cake pans. These were produced in the 19th century and depictions of them can be found in at least two books that I know of, one I own. 18th century recipes remain silent about the tins they should be baked in, but it is very possible that the then fashionable mince pie tins would have been used, leaving them without a need to create new tins….