Although spring is in the air at times and daffodils are showing their sunny faces hear and there, some days are still reminding us it is still winter. On cold grey days like these the central heating never seems to give enough warmth although the thermometer says otherwise. Baking seems to be the only antidote to dreary weather and puddings might just be the most fitting with their warming and filling character.

Puddings it is and although I have just published a 378 page book on the history of pudding… which was recently shortlisted for a prestigious André Simon Award (still pinching myself, and although I didn’t win, I am still chuffed to bits!), there are still so many pudding recipes left to boil, bake, steam, fry or freeze. Today I’m taking you to the Victorian era, when puddings were at the height of their splendour.

During Queen Victoria’s reign Britain was going through a period of industrial evolution and urbanisation. It was also a period of peace and stability. The 19th century saw the birth of the rail network with the steam locomotive as the greatest invention. This made for an enormous change in farming as food could now be transported to the towns more quickly and efficiently. On the land a lot of jobs had been replaced by new farming machines, techniques changed, unemployment and poverty rose as the population almost doubled. With more people moving to cities in search for work, demand for produce was high.

The contrast between the lives of the working class and the splendour in which the Queen lived was enormous. Victoria became queen in 1837 at the age of 18 but before that she lived in Kensington Palace which was at that time in quite a state of disrepair.

We know her mostly from her iconic photograph, in profile, dressed in black mourning clothes, looking stern and cold. She is the matriarch, the embodiment of a strong and powerful woman. But in reality she mourned the death of Prince Albert for the rest of her life and found it hard without him.

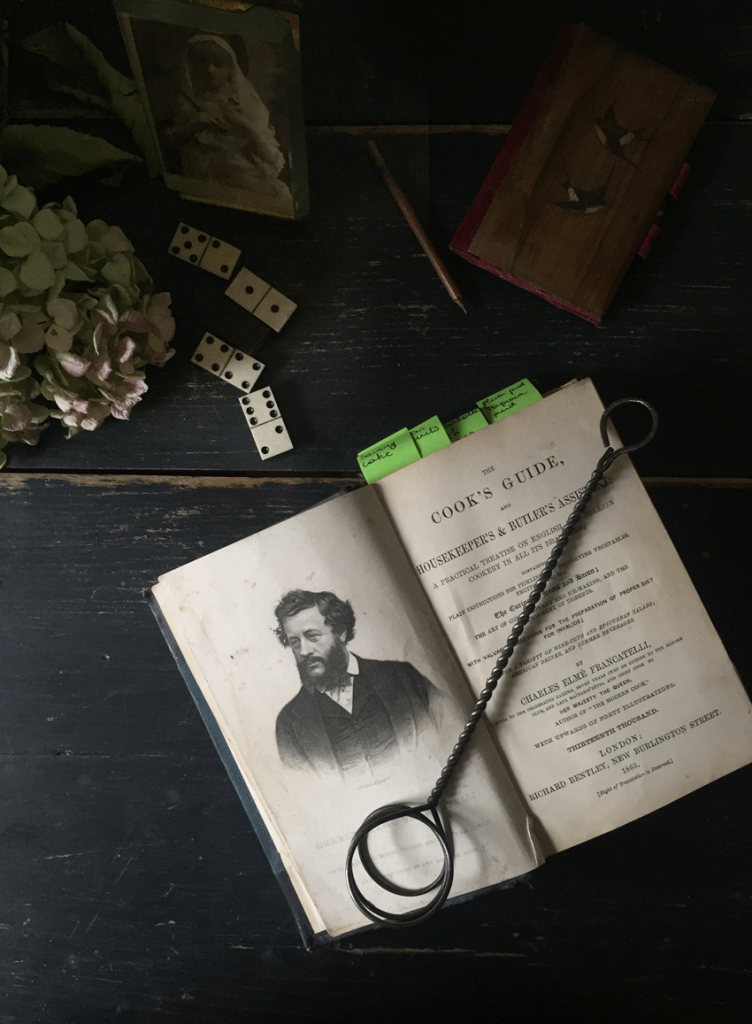

To know the story behind the portrait, the story of the woman, the queen and the widow, we were treated to an historical drama titled simply ‘Victoria’ recently. And this is the reason for this posting today. ‘Victoria’ is airing in America in March and that is why for the launch TV station KCTS9 and author Laurel Nattress asked me to recreate a pudding for Victoria and her husband Albert from a recipe by the queen’s then chef Charles Elmé Francatelli.

Television has changed so much because of the influence of social media. I would not have expected a tv series to give much attention to the cook in the past. But with food photos being one of the most popular snaps posted online, one can not ignore food and its importance.

In ‘Victoria’ therefore, we go down into the palace kitchens where master chef Charles Elmé Francatelli is at work. We see him developing recipes and treats for the queen and for his favourite maid, the dresser of the queen.

Francatelli took on the role as Chief Cook and Maître d’Hôtel to Her Majesty in 1840. Although it is easy to think he worked for the queen his whole career, in reality he stayed for only two years tops. But this didn’t stop him dedicating recipes in his books to Victoria, Albert and their children.

In total he published four books which went to several editions. He was possibly one of the most important chefs of his time. Francatelli was born in London but of Italian parentage. He studied in Paris before moving back to London to work for some notable noble households and gentlemen’s clubs. In 1850 he took over the Reform Club from Alexis Soyer, another important chef of this era. At some point he must have gotten annoyed with all the food wasted in high circles. He once remarked that “he could feed every day a thousand families on the food that was wasted in London“. Other than his books which were purely written for the upper classes he also wrote ‘A Plain Cookery Book for the Working Classes’ which included economical dishes such as cow-heel broth and bubble and squeak.

Even after watching ‘Victoria’ I’m still intrigued and eager to know more about this woman and her eating habits. Did she really like food, or was she indifferent to it and just ate to stay alive rather than live to eat.

Fortunately there will be a book soon that will tell us all about Victoria and her eating habits. The book is called ‘The Greedy Queen’ and it is written by my friend historian Dr. Annie Gray who also wrote the foreword to my book Pride and Pudding. You will also have seen her presenting Victorian Bakers on BBC.

Annie confirmed that the recipes Francatelli published were certainly eaten by the Queen:

Victoria adored food. Throughout her life she constantly sought out new tastes and flavours, and was always open to new things.”

The tv series is a great warmup to read the book, and lucky me has received a proof copy to read before its release date in may. This means you won’t have to wait long for a more detailed posting about this book which is in truth the most anticipated book of the year for me.

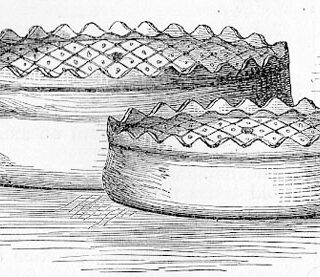

To celebrate the release of ‘Victoria’ in the United States I cooked two puddings from Francatelli’s books. One is the ‘Queen Pudding’ which is a baked pudding with glacé cherries, and the other is a steamed pudding called Biscuit pudding à la Prince Albert.

I asked Annie if there is any evidence that Victoria had a thing for pudding:

She was certainly a fan of pudding (and I mean pudding in the true sense, not in the modern sense). Even in old age she’d tackle both hot puddings and iced puddings with relish, and on one occasion, staying in a rather downmarket inn in Scotland, complained that there was ‘no pudding, and no fun’.

The Albert Pudding is blander in flavour, no spices are used, nor any dried fruits. Do you think that is who Albert liked his food?

Albert genuinely did prefer foods which were easier to digest and less highly flavoured. Francatelli’s rather muted recipe for Albert’s biscuit pudding therefore seems entirely in keeping with a man who ate purely to live – very much the opposite of his wife.

Queen Pudding (front pudding picture above)

What do you need

- 85 g castor sugar

- 85 g unsalted butter, room temperature

- 2 eggs

- 85 g all purpose flour

- 25 g glacé cherries, cut small

- 3 tbsp lemon juice

- grated zest of 1/2 lemon

- 1/2 tsp of baking powder

Preheat your oven to 180°C (350°F)

Butter a small baking mould or line with greaseproof paper. Cream butter and sugar together in a large bowl

Add the eggs one at the time and whisk for 5 minutes. Sift in the flour and baking powder and combine well.

Fold in the cherries, the zest and the lemon juice. Transfer the batter to the baking mould and bake in the middle of the oven for 45-50 minutes.

To test if the pudding is done, insert a toothpick and remove, when it comes out clean the cake is done, when you find raw batter on the toothpick it needs a little longer in the oven.

Albert’s Biscuit pudding

What do you need

- 170 g crumbled Savoy cake (see recipe) or leftover pound cake

- 120 ml pouring cream (30%fat)

- 2 egg yolks

- 1 egg white, whipped to a froth

- zest of 1/2 lemon

- 110 g caster sugar

First make your Savoy cake, you can do this a day in advance. The recipe will yield a little leftover cake.

Preheat your oven to 180°C (350°F) and bring a kettle of water to a boil

Line a pudding basin with a disc of greaseproof paper. Soak the cake crumbs in the cream in a large bowl for about 15 minutes, add the eggs, whites, zest and sugar and combine well.

Pour the batter into the pudding basin and cover the top with greaseproof paper or a towel. Get a large pot out and place an inverted plate on the bottom of the pot, place the pudding basin on top and fill the pot with boiling water up to half the height of the pudding basin.

Close the lid of the pot and carefully place the pot in the oven for 50 minutes.

Then remove from the oven and carefully take the pudding out of the hot water. Serve with Whip sauce or plain egg custard.

Savoy Cake

Makes enough for one 20 cm (8 inch) round cake

- butter, for greasing

- 25 g unsalted butter,

- softened

- 110 g caster sugar

- 2 eggs

- 1/2 teaspoon orange flower

- water, rosewater or lemon

- zest (optional)

- 110 g self-raising flour, plus extra for dusting

Preheat the oven to 180°C (350°F).

Grease the cake tin lightly with butter and dust with flour.

In a bowl, combine the butter and sugar together, adding the eggs one at a time and whisking thoroughly until the mixture is creamy. Add the flavouring, if using. Sift in the flour and fold in well. Pour the batter into the cake tin and bake in the middle of the oven for 30 minutes.

Insert a toothpick: when it comes out clean, the cakes are done. Do not open the oven before

30 minutes have passed or your cakes will collapse.

They should not have a lot of colour on top.

Keep the cake in an airtight container for up to 1 week.

Whip Sauce

- 4 egg yolks

- 55 g of caster sugar

- a shot glass of sherry or madeira

- 1 tbsp of lemon juice

- 1 tsp of lemon zest

- 1 grain of salt

This sauce needs to be cooked by using the “au bain marie” method, this means you need a pot of boiling water and another pot that fits on top so the pot or saucepan on top gets the heat from the water.

Bring water to a boil, in your saucepan combine the egg yolks, and the rest of the ingredients and whisk continuously until the mixture is frothy. Serve at once.

You might also enjoy

Cabinet Pudding, or what to do with stale cake

Fab post Regula with amazing photography (as always!).

Thank you Sam!! 🙂

I love this post. As I love Victoria. Unfortunately we’ve had only one season on Flemish television.

I think they are still filming it Anna, so we could be in luck for a season 2! 🙂

I have read — somewhere, in more than one book — that Victoria ate her food rather quickly; though not bolting it, as did Napoleon, which contributed to the stomach ailments that hastened his death and have been adduced by the French as evidence that he was poisoned by his captors, the dastardly English. When the Queen had finished what was on her plate all the dishes were whisked away, whether the other diners had concluded or not. This would not have done for me, who am a very slow eater. These puddings look good, and fun to make. Alas, I am diabetic and must go very easy on sweets.

Well Timothy I am reading exactly that in Annie’s book which really is one to buy when it comes out in may! It would not work for me either, I am a slow eater too, I chew my food more than 15 times before I swallow! I’m so sorry to hear you are diabetic! My friend just got diagnosed too and it is such a change!

i am genuinely loving your blog! this is so interesting to me, especially as while doing my undergraduate studies (in history) i considered becoming a food historian at one point because it’s all just really fascinating. and i love victoria and albert. so, obviously, i love this post and will have to start trying out all your recipes! i also need to get my hands on your book, because it sounds perfect. the puddings and photos in this post look gorgeous. xx

I love how you feature ethnic and traditional foods. My dad is from Edegem, Belgium and he always has cravings for Flemish food. I’ll try making some of your beautiful recipes!

I possess the decorative clay glazed Queen Pudding Mould. Would love to send a photo. And often wondered what it was for. And not only where it came from. It has a flavoured scent to it like a Belgian bakery would use. But I was told it was from Scotland. For a jelly mould… Plus, in France dainty cakes were called Fancy cakes? Though My Nanny used to call them dainty cakes. What you call Queen cakes. And I bought a Victoria & Albert tea service for my Eldest Niece. As when she was a little girl her dream was to come to England to take tea & cake with the Lovely English People. The last time I saw her was in 1983. I waited and waited and waited… She developed a malade unable to travel so I was told. Heart breaking news for her loving Auntie.