The meat of the heart is eaten quite commonly in Peru, but it might surprise some of you that for centuries is was also eaten in England. Beef heart is so unpopular I get mine from a local farm for as little as £3. That is great value for a huge piece of meat. I asked a couple of butchers, some in Belgium and also Borough Market. Beef heart is the kind of cut that doesn’t get sold and that is such a shame.

The meat of the heart is eaten quite commonly in Peru, but it might surprise some of you that for centuries is was also eaten in England. Beef heart is so unpopular I get mine from a local farm for as little as £3. That is great value for a huge piece of meat. I asked a couple of butchers, some in Belgium and also Borough Market. Beef heart is the kind of cut that doesn’t get sold and that is such a shame.

The flavour and texture of beef heart is like that of a good beefy steak because beef heart is a muscle just like steak is. I find beef heart great in any way it is cooked because it has so much flavour and it is very tender. In Peru they make kebab style roasted beef heart, in England beef heart was usually stuffed with a forcemeat.

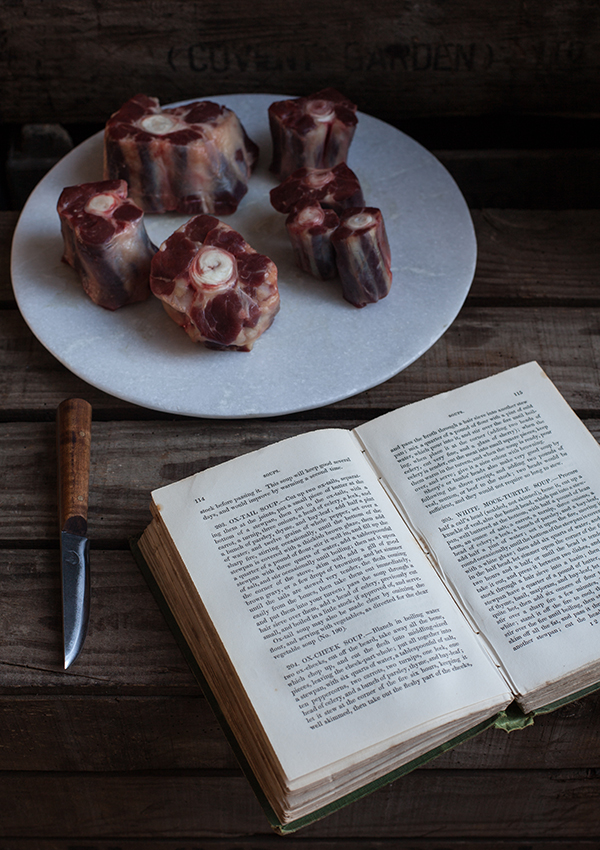

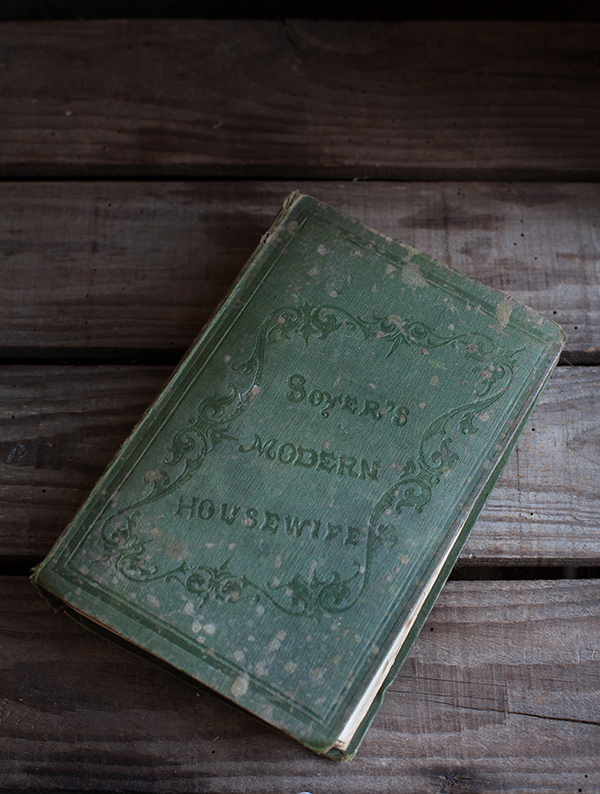

A couple of years ago I found a recipe for a stuffed beef heart in Elizabeth Raffald’s book The Experienced English Housekeeper (1769):

Wash a large beast’s heart clean and cut off the deaf ears, and stuff it with forcemeat as you do a hare, lay a caul of veal, or a paper over the top, to keep in the stuffing, roast it either in a cradle spit or hanging one, it will take an hour and a half before a good fire; baste it with red wine; when roasted take the wine out of the dripping pan and skim off the fat, and add a glass more of wine; when it is hot put in some lumps of red currant-jelly and pour it in the dish; serve it up and send in red currant-jelly cut in slices on a saucer.

The recipe was copied later by M. Radcliffe in her A Modern System of Domestic Cookery: Or, The Housekeeper’s Guide (1823) and it was also published in a later edition of Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery made Plain and Easy – A new Edition (1803). The recipe dit not appear in the first edition of 1747. Copying recipes from other cooks was common practice in those days and they were often copied word for word, making it easy to determine their source.

To make this dish slightly lighter I opted to stuff the heart with a duxelles, which is a mixture made with mushrooms, bacon and in this case kale or cavolo nero. If I had caul – a thin lace-like membrane which surrounds the stomach internal organs of some animals – like Raffald suggested, I would have used it as it keeps in the stuffing in nicely and tidy. But if you can not obtain it, some creative string-work will do the trick just fine.

…