Marmalade is like Marmite, you either love it or loathe it.

Marmalade is loved in Britain, smeared on golden toast as the last course of the English Breakfast. The humble jar of sunshine even has its own Marmalade Awards each year in Cumbria in the North of England. Anyone can send in their jar to be judged by marmalade royalty, and my friend Lisa from All Hallows Cookery School in Dorset just won with hers.

In a time when bitter flavour is bred out of vegetables and fruits, you would think many people are not that fond of marmalade. Marmalade is traditionally made from bitter Seville oranges. Originally from Asia, the Moors introduced these oranges in Spain around the 10th century. They are quite inedible in their raw state and if you can manage I salute you. Because of their sourness Seville oranges contain a high amount of pectin. In 17 and 18th century cookery books they get a mention as ‘bitter oranges’ and it wouldn’t be an British classic without a story.

The legend

In the mid 18th century a Spanish ship carrying Seville oranges was damaged by storm. The ship sought refuge in the harbour of Dundee in Scotland where the load deemed unfit for sale were sold to a local merchant called James Keiller. James’ mother turned the bitter orange fruit into jam and so created the iconic James Keiller Dundee Marmalade. It wasn’t a coincidence that James mother made marmalade, in the 1760s her son ran a confectionery shop producing jams in Seagate, Dundee. In 1797 he founded the world’s first marmalade factory producing the first commercial brand of marmalade. In 1828, the company became James Keiller and Son, when his son joined the business. Today you can see stone James Keiller and Son marmalade jars pop up at every carboot sale and antiques market. But the marmalade is still in production, only now in glass jars that off the beautiful radiant orange colour that is so typical of marmalade.

The truth as clear as marmalade

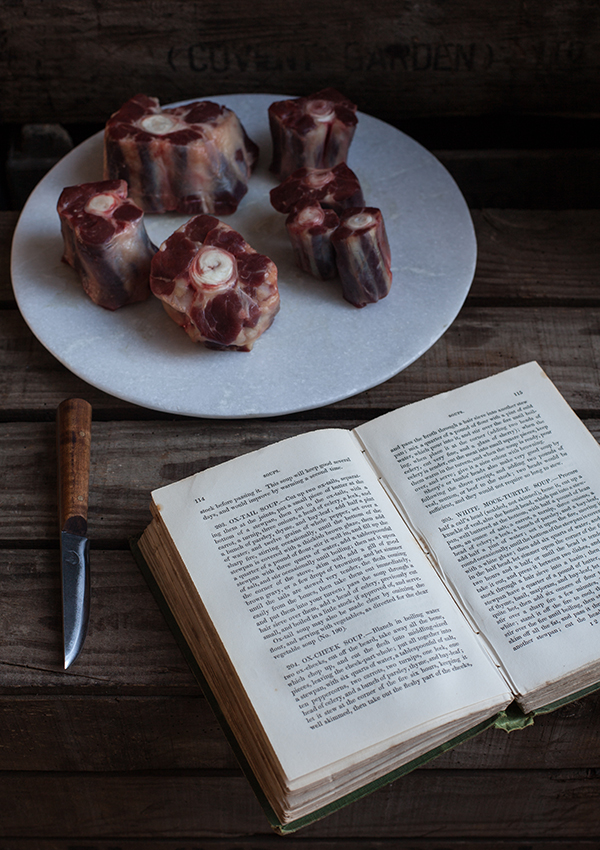

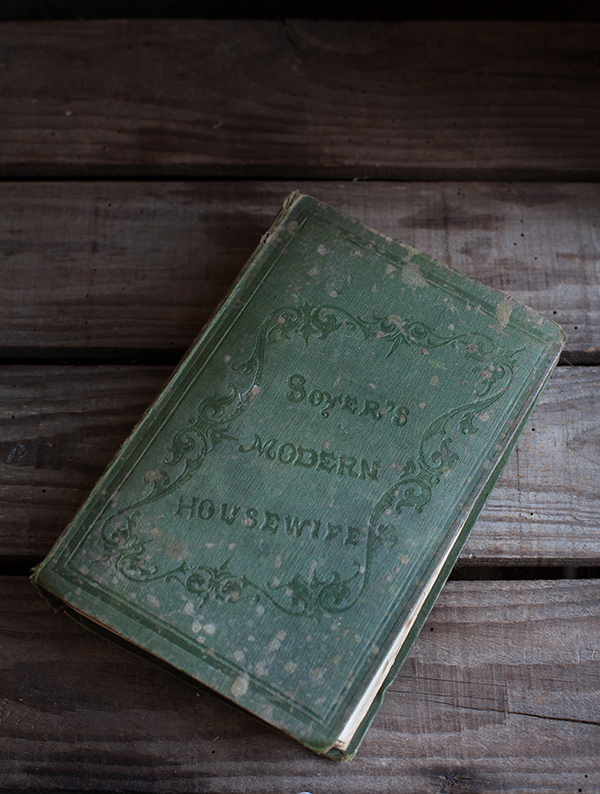

According to Ivan Day, a prominent food historian who I was lucky to do a course with, one of the earliest known recipe for a Marmelet of Oranges dates from around 1677 and it can be found in the recipe book of Eliza Cholmondeley held in the Cheshire Archives and Local Studies.

The earliest recipe in Scotland is titled ‘How to make orange marmalat’ and dates back 1683. It can be found in the earliest Scottish manuscript recipe book which is believed to have been written by Helen, Countess of Sutherland of the Clan Sutherland. The book is dedicated entirely to fruit preservation and jelly making. According to The Scotsman “The Countess was married to John Gordon, the 16th Earl of Sutherland, an army officer who was honoured following the defeat of the 1715 Jacobite rebellion.”

This bit of information transports me right to the wuthering heights of Scotland.

This early Scottish as well as English recipe debunks the myth that mother Keiller invented marmalade. Recipes for similar preserves even date back earlier in history. But the Keiller family definitely deserve a prominent spot in marmalade history.

But why do we call it marmalade and not jam?

As you maybe remember from my posting about ‘Quince Cheese’ here > , quinces are responsible for the word marmalade as their Portuguese word is ‘marmelo’ and they were made into fruit cheeses named marmalades. In Spain they call it ‘Membrillo’. Quince just like bitter Seville oranges, contain a lot of pectin and they are both too sour to eat raw. From both of these fruits the pips and peels are used to get a good set, and if you don’t have quince you could easily make a fruit cheese out of these oranges….