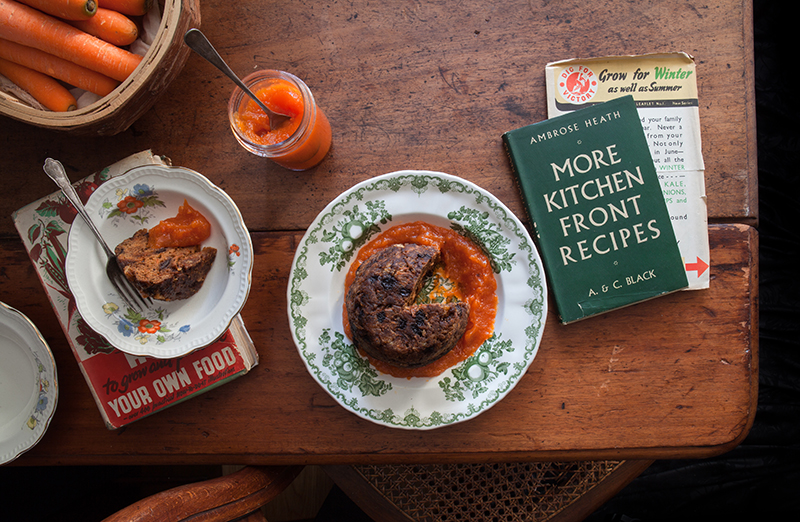

Today 8 may I’ll be showing two war-time recipes over at London’s Borough Market for the 75th anniversary of ‘Victory in Europe Day’ or the end of WWII.

While world wars and lockdown are very different, both have led to difficulties obtaining certain ingredients. We’ll be looking at two war-time recipes that were actually promoted by the Ministry of Food because there was an overload of carrots and potatoes. Recipe booklets were made to help cooks to whip up a variety of recipes with carrots and potatoes and other austere but often very delicious creative recipes…

Food & Social history

Brighton Rock Cakes – from Oats in the North, my new book

Recipe and extract from Oats in the North, Wheat from the South, published with Murdoch Books and available here >

Recipe and extract from Oats in the North, Wheat from the South, published with Murdoch Books and available here >

Usually these buns appear as ‘Rock cakes’ or ‘Rock buns’ in old cookery books, but in 1854 two recipes for Brighton rock cakes appeared in George Read’s The Complete Biscuit and Gingerbread Baker’s Assistant. Read gives a recipe for Brighton rock cakes and another for Brighton pavillions. The latter are made the same way as Brighton rock cakes, but are finished with a topping of currants and coarse sugar that, he says, should be ‘as large as a pea’.

You can still buy Brighton rock cakes in the seaside town of Brighton at the Pavilion Gardens Café. The open-air kiosk at Brighton Pavilion has been selling Brighton rock cakes since 1940, and possibly even longer if we look at Read’s recipe from 1854. Rock cakes are popular throughout Great Britain and Northern Ireland, and often appear in literature. In Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, Hagrid serves them to Harry and Ron, and Agatha Christie also mentions them in more than one novel.

I wanted to share this recipe in publication week of my new book Oats in the North, Wheat from the South because currently I am missing the sunny Brighton beach, the buzzing pier, and the busy Brighton lanes with its independent shop walhalla. I miss the days without worry when we drove over to the UK for a weekend, antiquing, walking, eating… When the Corona crisis is over I’m planning a trip, but I wonder how we will feel post Corona, will we be free of worry or will the way we live change?

But for now, we can bake, do join my #bakecorona on social media.

This recipe only uses one egg, in a time when eggs are dear this recipe might be a solution, other recipes from the book which can be handy during shortages are the Soda bread – to save yeast, the Parkin – to save sugar, the Cornish Heavy cake NO eggs at all, Yorkshire parkin – just oat flour needed, the fat rascalls – just 1 egg needed, Swiss roll – no baking powder but lots of eggs, Flapjack – uses just oats or leftover muesli. And to save an egg, I use an egg less in my pound cake! Happy baking…

This recipe for Brighton rock cakes contains candied cedro, but most rock cakes only contain currants, so you can easily leave it out.

Recipe from Oats in the North, Wheat from the South, published with Murdoch Books and available here >

For 6 rock cakes

- 225 g plain (all-purpose) flour

- 100 g raw cane (demerara) sugar or white sugar

- 1 tsp baking powder

- 1/4 tbsp mixed spice

- pinch of sea salt

- 75 g chilled butter, diced

- 1 egg

- 3 tbsp full-fat milk

- 50 g currants

- 30 g candied cedro (optional)

- 3 glacé cherries, halved, to garnish (optional)

- nibbed sugar, to garnish (optional)

Method

Preheat your oven to 200°C (400°F) and line a baking tray with baking paper.

Mix the flour, sugar, baking powder, mixed spice and salt in a large bowl. Add the butter and rub it into the flour mixture until it has the consistency of breadcrumbs.

Stir in the egg, then add enough milk to bring the dough together without making it too wet. If the dough is too dry to press together, add a teaspoon of milk. Fold the currants and candied cedro through the dough. Form six rock cakes using two forks – this will help achieve a rugged, rocky look. Place on the baking tray and decorate with the cherries and sugar, if using. Bake in the middle of the oven for 15 minutes until the rock cakes have a golden blush.

Buns for Saint Hubert: Mastellen from Ghent

The city of Ghent ’s most famous bake is called ‘Mastel’ and it is a soft bun flavoured with cinnamon shaped into a round with a dimple in the middle made by pressing down four fingers in the dough. The name Mastel comes from ‘masteluin’ a bread mixture made with wheat and rye flour, it was an old practice to grow the two grains mixed on one single field to improve yield. Since medieval times the bun was consecrated by a priest and eaten as a preventative against hydrophobia or rabies on the feast of St Hubert on 3 november. Today the bun is often blessed on the 3rd of november but no one really believes it will protect them from hydrophobia or rage.

The city of Ghent ’s most famous bake is called ‘Mastel’ and it is a soft bun flavoured with cinnamon shaped into a round with a dimple in the middle made by pressing down four fingers in the dough. The name Mastel comes from ‘masteluin’ a bread mixture made with wheat and rye flour, it was an old practice to grow the two grains mixed on one single field to improve yield. Since medieval times the bun was consecrated by a priest and eaten as a preventative against hydrophobia or rabies on the feast of St Hubert on 3 november. Today the bun is often blessed on the 3rd of november but no one really believes it will protect them from hydrophobia or rage.

Mastellen are also sold dried to use for making a pudding called ‘Aalsterse Vlaai’ and the dried out bun was also often soaked in buttermilk to eat as a gruel. A custom that is in decline is that of the ‘ironed mastel’ where a mastel bun is sliced in two and spread with butter and a generous topping of brown sugar. The bun is then crushed under the weight and heat of an old fashioned heavy cast iron well eh – iron. The kind that used to be kept on the stove. The result is a crisp biscuit that resembles a Lackman waffle. Truly delicious. This ironing of the mastel is popular on the first weekend of august in the Ghent area called Patershol during the Patershol feasts, a jolly folk festival in one of Ghent’s most culturally diverse area, it is therefore also called Coté Culture. (Patersholfeesten are his weekend if you’re in the area! Also check previous post on where to go and eat in Ghent – I will be adding to this post over time.)

The custom of eating consecrated bread on St Huberts day comes from the story that the saint cured a man of rabies by giving him bread to eat. St Hubert was the Bishop of Liege and the patron saint of hunters, on the 3rd of november an event takes place in Liege where the hunting hounds, masters and staff are blessed by a priest. This date also marks the start of the hunting season….

Hot Cross Buns – The Tale Of English Buns # 2

Bake them on Good Friday: The history and tales behind these spiced buns are plenty and intriguing, steeped in folklore dating back as far as Anglo-Saxon Britain. This is perhaps one of the most iconic of buns. Recipe from my new book Oats in the North, Wheat from the South, out with Murdoch Books (2020)

Bake them on Good Friday: The history and tales behind these spiced buns are plenty and intriguing, steeped in folklore dating back as far as Anglo-Saxon Britain. This is perhaps one of the most iconic of buns. Recipe from my new book Oats in the North, Wheat from the South, out with Murdoch Books (2020)

Every year well before Easter Marks & Spencer starts piling up Hot Cross Buns from chocolate & salted caramel to blueberry and marmalade. Marmalade I can understand as you do add candied orange peel to the dough, but chocolate & salted caramel and blueberry just creates a whole different bun, the cross being the only reminder of a traditional Hot Cross Bun. But what is traditional or original with a recipe as old as this one? If you scroll down to the recipe you might discover I too dare to add something which isn’t traditional from time to time.

The tradition of baking bread marked with a cross is linked to paganism as well as Christianity. The pagan Saxons would bake cross buns at the beginning of spring in honour of the goddess Eostre – most likely being the origin of the name Easter. The cross represented the rebirth of the world after winter and the four quarters of the moon, as well as the four seasons and the wheel of life.

The Christians saw the Crucifixion in the cross bun and, as with many other pre-Christian traditions, replaced their pagan meaning with a Christian one – the resurrection of Christ at Easter. …

Bitter Seville Orange Marmalade – A Potted History and How to Make it

Marmalade is like Marmite, you either love it or loathe it.

Marmalade is loved in Britain, smeared on golden toast as the last course of the English Breakfast. The humble jar of sunshine even has its own Marmalade Awards each year in Cumbria in the North of England. Anyone can send in their jar to be judged by marmalade royalty, and my friend Lisa from All Hallows Cookery School in Dorset just won with hers.

In a time when bitter flavour is bred out of vegetables and fruits, you would think many people are not that fond of marmalade. Marmalade is traditionally made from bitter Seville oranges. Originally from Asia, the Moors introduced these oranges in Spain around the 10th century. They are quite inedible in their raw state and if you can manage I salute you. Because of their sourness Seville oranges contain a high amount of pectin. In 17 and 18th century cookery books they get a mention as ‘bitter oranges’ and it wouldn’t be an British classic without a story.

The legend

In the mid 18th century a Spanish ship carrying Seville oranges was damaged by storm. The ship sought refuge in the harbour of Dundee in Scotland where the load deemed unfit for sale were sold to a local merchant called James Keiller. James’ mother turned the bitter orange fruit into jam and so created the iconic James Keiller Dundee Marmalade. It wasn’t a coincidence that James mother made marmalade, in the 1760s her son ran a confectionery shop producing jams in Seagate, Dundee. In 1797 he founded the world’s first marmalade factory producing the first commercial brand of marmalade. In 1828, the company became James Keiller and Son, when his son joined the business. Today you can see stone James Keiller and Son marmalade jars pop up at every carboot sale and antiques market. But the marmalade is still in production, only now in glass jars that off the beautiful radiant orange colour that is so typical of marmalade.

The truth as clear as marmalade

According to Ivan Day, a prominent food historian who I was lucky to do a course with, one of the earliest known recipe for a Marmelet of Oranges dates from around 1677 and it can be found in the recipe book of Eliza Cholmondeley held in the Cheshire Archives and Local Studies.

The earliest recipe in Scotland is titled ‘How to make orange marmalat’ and dates back 1683. It can be found in the earliest Scottish manuscript recipe book which is believed to have been written by Helen, Countess of Sutherland of the Clan Sutherland. The book is dedicated entirely to fruit preservation and jelly making. According to The Scotsman “The Countess was married to John Gordon, the 16th Earl of Sutherland, an army officer who was honoured following the defeat of the 1715 Jacobite rebellion.”

This bit of information transports me right to the wuthering heights of Scotland.

This early Scottish as well as English recipe debunks the myth that mother Keiller invented marmalade. Recipes for similar preserves even date back earlier in history. But the Keiller family definitely deserve a prominent spot in marmalade history.

But why do we call it marmalade and not jam?

As you maybe remember from my posting about ‘Quince Cheese’ here > , quinces are responsible for the word marmalade as their Portuguese word is ‘marmelo’ and they were made into fruit cheeses named marmalades. In Spain they call it ‘Membrillo’. Quince just like bitter Seville oranges, contain a lot of pectin and they are both too sour to eat raw. From both of these fruits the pips and peels are used to get a good set, and if you don’t have quince you could easily make a fruit cheese out of these oranges….

Jumbles on the battlefield

It has been a busy few months, flying from photography assignments and meetings in London to Latvia for research, London again, then to New York, two days after to Milan, then London again, then Milan again a few days ago. I have been spreading myself too thin, so over the Easter weekend, my first weekend home since somewhere in februari, I barricaded myself onto the sofa between stacks of pillows and two sleepy cats.

It has been a busy few months, flying from photography assignments and meetings in London to Latvia for research, London again, then to New York, two days after to Milan, then London again, then Milan again a few days ago. I have been spreading myself too thin, so over the Easter weekend, my first weekend home since somewhere in februari, I barricaded myself onto the sofa between stacks of pillows and two sleepy cats.

We are talking Jumbles today and I don’t mean gibberish.

I was following ‘A History of Royal Food and Feasting’, a fun free online course from the University of reading and Historic Royal Palaces with a lot of interesting historical information about food. A lot of the information I already knew but I did manage to learn a few things, plus it was just great fun to do and force myself to take some rest while still being productive. One of the dishes that were recommended to try on the course were Jumbles, a biscuit I had been meaning to bake but haven’t had the time in my mad schedule. When the Learning and Engagement department got in touch to check if I wanted to get involved to spread the word about the course I of course said yes because I enjoyed it. So Jumbles it was!

Jumbles were knot shaped biscuits that first appeared in the wonderful book The good Huswifes Jewell by Thomas Dawson, dating to 1585. But legend places this biscuit right at the heart of The War of the Roses a century before Dawson’s recipe.

For those who are unfamiliar with English history The Wars of the Roses were a series of battles fought in the period of 1455 to 1485 between two rival branches of the royal House of Plantagenet, the House of York and the house of Lancaster – both sporting a rose in their heraldic emblem. Both made a claim for the throne of England. They were a result from the social and financial problems following the Hundred Years’ War. The Lancastrian claimant, Henry Tudor defeated the last king of the House of York, Richard III at Bosworth Field, near Market Bosworth, a market town in Leicestershire. He then married Edward IV’s daughter, Elizabeth of York, to unite the two houses.

And it is precisely on this last battlefield that a new legend was born, at least a few centuries later……

Stir-up Sunday, History and Plum pudding

Let me start with blowing my own trumpet, it’s my blog so I’m allowed! I’m pleased to have tracked down a copy of Delicious Magazine while in Budapest because in it they have elected my book Pride and Pudding as one of the best books of 2016! After the hard work creating this book I am of course flattered and beyond happy to get this kind of news! So thank you again Delicious Magazine UK!!

Now on to the news of the day!

This weekend will mark the last Sunday before advent which is traditionally Stir-up Sunday. According to (rather recent) tradition, plum pudding or Christmas pudding should be made on this day. It is a custom that is believed to date back to the 1549 Book of Common Prayer (though it is actually not); where a reading states ‘stir up, we beseech thee’. The words would be read in church on the last Sunday before Advent and so the good people knew it was time to start on their favourite Christmas treat.

It was a family affair: everyone would gather to stir the pudding mixture from east to west, in honour of the Three Kings who came from the east. Sometimes coins or trinkets would be hidden in the dough; finding them on Christmas Day would bring luck and good fortune.

There are a lot of legends and claims made about the origins of the plum pudding. Some say it was King George I who requested plum pudding as a part of the first Christmas feast of his reign, in 1714. George I was christened ‘the Pudding King’ because of this myth but there are no written records prior to the twentieth century to tell us that this king deserved this title.

…

Bakewell puddings and Bakewell tarts

It was Bakewell tart on Great British Bake Off yesterday last week! And when Mary said this is what a Bakewell tart should look like… I had to disagree. Traditionally early Bakewell tarts did not have a topping of icing. Nor do they have that lonesome cherry which we associate with cheap shop bought mini-bakewell tarts. Mary’s Bakewell tart didn’t have the cherry but did have the icing with a fancy pattern. It looked the part, don’t get me wrong, but if you visit the town of Bakewell you will see that proud Bakewell tart bakers clearly state that they do not add icing to their Bakewell tarts as icing is not part of the original recipe… But what is the original recipe? When does it stop or start being original? It’s a tough question.

And then there’s that other Bakewell bake… The Bakewell pudding!

Imagine a pub in a quintessentially English village: you enter with an appetite and the special on the menu is a pudding named after that village. You just have to try it, don’t you? And so the Bakewell pudding rose to fame. Even though Wonders of the Peak, the first travel guide to the Peak District, was written by Charles Cotton in 1681, tourism reached a high in Victorian times, helped by the development of the railway and an increasing interest in geology. Victorians also came to ‘take the waters’ in the spa towns of Buxton, Matlock Bath and Bakewell….

Cabinet Pudding – Or what to do with stale cake and booze

Let me share with you a recipe from Pride and Pudding, my debut book that was festively launched in London’s Borough Market two weeks ago. There is also good news if you haven’t ordered the book yet! The Amazon editorial team has not only included Pride and Pudding in their ‘Books of the Month’ – this week it is also part of their ‘Deal of the Week’ which comes with a 50% discount only this week. (Get it here >) Meaning it will only set you back a tenner! It looks like sales are going splendid as I haven’t seemed to have lost my spot in the first 10 of the top 100 Bestsellers. As an author you do fear no one will buy your book. As do you fear bad reviews and negativity. So if you have a moment and you like the book, Amazon reviews do make a difference.

Now back to the actual order of the day. Cabinet pudding was a favourite on Victorian tables, the first recipes for it appeared in the early 19th century, though similar puddings had been made long before then. It is also sometimes called Newcastle pudding, diplomat pudding or Chancellor’s pudding, though the connection with politics isn’t clear. Recipes also vary. There are theories about the name but none seemed to hold much truth to them….

Bath buns – or the tale of English buns #1

If you have visited the city of Bath, nestled in a green valley with its Roman baths, elegant Georgian townhouses and impressive circus, you might have noticed that there are two famous buns in town. Both are competing to be the oldest, most authentic, and most valuable to the city’s heritage. The Sally Lunn and the Bath Bun – they both even have their own tea room in town. Of course the notion that one of these buns is more important than the other is bollocks. At the end of the day, it’s just something to spread your butter on. I’m far more interested in both of these buns history than I am in their importance.

If you have visited the city of Bath, nestled in a green valley with its Roman baths, elegant Georgian townhouses and impressive circus, you might have noticed that there are two famous buns in town. Both are competing to be the oldest, most authentic, and most valuable to the city’s heritage. The Sally Lunn and the Bath Bun – they both even have their own tea room in town. Of course the notion that one of these buns is more important than the other is bollocks. At the end of the day, it’s just something to spread your butter on. I’m far more interested in both of these buns history than I am in their importance.

One bun maker claimed that the Bath bun was just simply a Sally Lunn which was slightly changed and then given the name Bath Bun for the tourists. A rather simplistic way of looking at it, but it has happened to other foods in the past. Of course in this case we are talking about two entirely different buns.

What a difference a bun makes

We know that during the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, set up by Prince Albert, 934.691 Bath buns were sold to the public. This shows they were either popular, or they were the best option! According to bun legend people remarked that the Bath bun sold in London was not exactly like the one sold in Bath and soon Bath buns in London were renamed London buns. However, mentions for London buns can be found 20 years before the Great Exhibition. So I’m fairly sure we are again talking about two different buns. To confuse things even more is that in Australia a Chelsea bun is known as a London bun.

The Sally Lunn which I will get to in another posting, is a light bun with a nice dome shaped top, it looks like a brioche but is less rich and not sweet at all. It is known since 1776. The Bath bun used to be a Bath cake in the 18th century. But although it was called cake, it was definitely treated as a bun, which according to Elizabeth Raffald The Experienced English Housekeeper, 1769 should be the size of a French roll and sent in hot for breakfast. Bath resident and cookery author Martha Bradley, gave a recipe in her book in 1756 entitled ‘Bath seed Cake’. Over the course of the 18th century eggs were added to the batter making the buns richer. In Andre Simon’s ‘Cereals: A Concise Encyclopedia of Gastronomy’ from 1807 the recipe instructs the cook to:

Rub 1 lb. of butter into 2 lb. of fine flour; mix in it 1 lb. of caraway comfits, beat well 12 eggs, leaving out six whites, with 6 spoonfuls of new yeast, and the same quantity of cream made warm; mix all together, and set it by the fire to rise; when made up, strew comfits over them.

Jane Austen was a fan of Bath buns and promised to stuff her face with them if her sister Cassandra would not be joining her for a visit to Paragon that May….